Titus de Bobula

Portrait of Titus de Bobula from The Cement Era, 1907

Update: As we learn more about Titus de Bobula, this article continues to change, and much of what earlier versions asserted as fact was wrong. As of now, however, this humble sketch appears to be the most thorough biography of Titus de Bobula on the Internet. Our latest additions are a substantial expansion of his early career in Ohio and a glimpse of Mr. and Mrs. De Bobula as an old couple living in poverty in the early 1950s.

Titus de Bobula was one of our most important early modernists, and certainly the one whose style was the most eccentric by Pittsburgh standards. From a technical point of view, his influence was enormous: he introduced reinforced concrete to building construction in Pittsburgh. Yet it has been difficult to find much good information about him. He pops up most often as a footnote to Frederick Scheibler; yet, but for the happy accident of failing to become Nazi dictator of Hungary, de Bobula might have made Scheibler his footnote. This article, which will be revised as often as necessary, will gather whatever interesting fragments we can round up.

Titus de Bobula (1878–1961) was the son of János Bobula Sr. (1844–1903), a Hungarian architect who has left many fine buildings in Budapest. Bobula was also a journalist and politician, and two of his sons grew up to be architects: János Jr., who gave Budapest some fine buildings, and Titus, who accumulated a “de” in his name, possibly because he found it would impress Americans more than the bare “Bobula.”1 Titus would also inherit his father’s political bent, though he would bend it in a different direction: János Sr. was a liberal, whatever that meant in Hungary of the 1800s.

In Ohio

At some time about 1897 Titus arrived in the United States. We have heard that he worked briefly in New York, but we first catch sight of him in Ohio in June of 1901, when a Marietta paper ran this story on the front page:

Titus de Bobula has accepted a position with the W. B. O’Neill Co. and has already entered upon the performance of his duties. Mr. de Bobula is an Hungarian by birth, and was graduated from the Polytechnic Academy at Buda Pest. He has visited France, Germany, Greece, Russia and Egypt and studied the architecture which in ancient and modern times has characterized these countries. He is an accomplished linguist besides being an expert colorist, draughtsman and constructionist.2

We shall find as we go on that this is a typical De Bobula notice, magnifying his accomplishments and doubtless repeating information the reporter got from De Bobula himself. Wherever he went, he managed to convince the people around him that they had come face to face with someone unusually impressive—at least until they got to know him better.

The job with W. B. O’Neill does not seem to have lasted very long. In August we find De Bobula involved in the moving of a church hall for the St. Mary’s congregation in Marietta, which was about to start building a magnificent new church, designed by the Cleveland architect Emile M. Uhlrich, and now known as the Basilica of St. Mary of the Assumption.3 This probably means he was already a local representative of the Chicago house-moving firm of L. P. Friestedt, as we find from a notice on September 26.

Professor M. R. Andrews employed L. P. Friestedt, the Chicago house-mover expert, to raise his residence on Front and Wooster four and a half feet. The work was begun yesterday and finished today. The extraordinary quickness with which the work was performed, showed Mr. Friestedt’s ability, house-owners will do well to employ him to raise their homes out of high water and will feel themselves satisfied with his work. The superintendents are architects de Bobula and Sanderson, who are Mr. Friestedt’s representatives here and to whom all inquiries are to be referred.4

We hear nothing more of Sanderson; if this was a partnership, it was very short-lived.

On November 28, we hear of young De Bobula taking on a fairly big project in Cambridge, Ohio:

Architect Titus de Bobula, of Marietta, has prepared plans for a $30,000 business block to be erected by S. A. Craig on the corner of Wheeling avenue and South 8th street.5

If this was built—and we shall find as we go on that most of De Bobula’s grandest projects were never built—it no longer exists. A modern city hall stands on the probable site.

In 1902, De Bobula ran this advertisement in the American School Board Journal for several months running:

We believe this is, so far, the earliest drawing anyone has found attributable to Titus de Bobula.

Note the “main office”; by this time, De Bobula seems to have moved to Zanesville and taken an office in the Old Citizens Bank Building.

We do not know whether this school was ever built, and we have some reason to believe it was not. A school of similar age and size still stands in Byesville (you can see it on Google Street View), but it is not at all the same building. Perhaps a reader from Ohio can inform us. For reasons that will become obvious as we follow his story, we have to suspect anything De Bobula tells us about himself. In that context, by the way, we should mention that advertising was considered “unprofessional” in architects’ codes of ethics.

In August of 1902, De Bobula advertised for an “energetic young draftsman,”6 and then two days later placed two want ads in the Zanesville Times Recorder:

Plans and specifications for the first of five churches in Allegheny city, Pa. and neighborhood, will be on file in my office from the 1st to the 8th of Sept. Cost $22,000. Bids to be submitted to me on or before the 8th of Sept. Architect De Bobula.

WANTED—Three pressed brick layers at once. Architect De Bobula, Old Citizens Bank Building.7

This must have looked like his big break. Pittsburgh (with its neighbor Allegheny, soon to be absorbed) was the big city, and it was booming. He had a church in the works, and four more— Well, we don’t know how real those four more jobs were. We’ll find our subject has a consistent tendency to exaggerate numbers as we go on with Titus de Bobula’s career.

In the October 1, 1902, issue of the Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, a journal that chronicled construction throughout Pennsylvania, we find this notice:

At Allegheny, Pa., Rev. Father John Korotnoki, 591 Preble avenue, or Titus De Bobula Zanesville, Ohio, architect will receive bids for stained glass, seating and hardware for the new Greek Catholic Church.

The address 591 Preble Avenue was in a dense and lively neighborhood of Allegheny called Woods Run, now completely obliterated. Fr. Korotnoki or Korotnoky was the first pastor of Holy Ghost, a Ruthenian parish, and the church went up on Doerr street, just around the corner from his address and just across the street from the Western Penitentiary. A parking lot occupies the site now.

On March 26, 1903, a notice appeared on page 7 in the Zanesville Signal: “Architect De Bobula, formerly of Main street, is moving his offices to Pittsburg, where he expects to be located on or about April 1.”

In Pittsburgh

Titus de Bobula’s address in Pittsburgh for the next few years would be an office in the most prominent building in the city, the Farmers Bank Building, a skyscraper designed by the redoubtable Alden & Harlow. As soon as De Bobula arrived in Pittsburgh, he was taking on big jobs and planning bigger ones. He was building some important churches, about which more in a moment. But some of his plans were colossal. Less than a year after his arrival in Pittsburgh, we read a notice in a construction journal:

It is said that Architect Titus De Bobula, Farmers Bank Building, will be ready in a short time for bids for the erection of the Alpha Apartment Hotel at East End and Penn avenues. The structure will be finely finished throughout and will be provided with all the modern conveniences. The cost will be about $400,000.8

De Bobula seems to have become something of an architectural celebrity for a while. He was boldly advocating new things in materials and style, and people all over the country took notice.

Here is how he presented himself in a Pittsburg Press roundup of local architects in 1905, where it looks as though the architects provided their own profiles:

Titus de Bobula

Architect Titus de Bobula, whose offices are in the Farmers Bank building, was born in Hungary; attended the Polytechnicum in Budapest, Karlsruhe, Germany, and the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. After his travels all around the world, on his third visit to the United States, he established himself in Ohio, where he has built several ecclesiastical and buildings [sic]. He moved to Pittsburg when the Farmers Bank building was ready for occupancy. To his judgment, America is big and strong enough to have an art of her own, not only in skyscrapers, but in court houses, churches and all other public and private buildings. His last two years’ work in Pittsburg and vicinity includes churches, parish buildings, schools, residences and hotels, several of which are finished and occupied.9

Representing Titus de Bobula’s work was a photograph of a “Glen Tenement,” which still stands in Hazelwood:

Tenement House in Hazelwood

It is a very ordinary design by de Bobula standards, but it has held up for 120 years with few alterations.

In that same year, the Architectural League of America (a group of architects who thought the AIA was not progressive enough) held its convention in Pittsburgh, and Titus de Bobula read a paper that earned much attention from the architectural press. The subject was “American Style,” and you will be pleased to know that de Bobula traces the roots of human civilization to America, with Atlantis as the intermediary that spread American ideas to the Old World. Because it is a window into the mind of our subject, we have reprinted the whole text of De Bobula’s “American Style” on a separate page.

De Bobula seems to have been a very skillful self-promoter, to put it in the kindest way, and writers on architecture knew they could rely on him for what we today would call a sound bite from the modernist point of view. He was especially often quoted in magazines for the concrete trade, for the obvious reason that he was one of the earliest architects to employ reinforced concrete in houses and churches as well as commercial buildings. From Cement World, January 15, 1909:

Pittsburgh has made some fine advances in the matter of cement and reinforced concrete houses. The first architect to take up this matter seriously was Titus De Bobula, who put his ideas in practice in some twenty houses10 which he built in the Greenfield section for Eugene O’Neil, a multi-millionaire newspaper owner of Pittsburgh.11 These houses were built in rows and contain nine rooms and bath with front and back porches and cabinet mantels. Their cost complete was $1,680 each. The walls and partitions were reinforced concrete. All floors were concrete with white pine over floors in the living-rooms. The roofs were concrete with asphalt water-proof and also outside walls were water-proofed with a special colorless compound. Other houses similar to these have since been built in the Mt. Lebanon district and are popular sellers. The cleanliness, healthfulness and beauty of these houses when properly tinted, makes them among the best selling dwellings in Pittsburgh; and they are all works of art.

Incidentally, those Greenfield houses had gone a little over budget. From Concrete in 1905:

Architect Titus de Bobula, with offices in the Farmers’ Bank, is building for Mr. E. M. O’Neill on Frank Street and Greenfield Avenue a row of 160 [probably a misprint for 16] two-story concrete houses. The fronts will be faced with La Farge cement and the floors and roof will be of reinforced concrete. The houses will be absolutely fire-proof throughout and the cost will be $1500 for each house. Mr. de Bobula claims that this figure is less than the same house could be built of common brick or frame. Mr. Howard B. Manley has been awarded the contract for the construction of the first six houses. Each house will have five rooms and a bath.

There is some mystery about these houses. Most of the few writers who mention them seem to accept that all the houses were built, but old Pa Pitt believes, having checked the old maps, that only the six we see now, plus three on Lilac Street that have since been replaced by two larger postwar houses, were ever built. Rows of similarly sized houses went up on Greenfield Avenue on either side of Frank Street at about the same time, and on property that used to belong to Eugene O’Neill, but they are of brick—as the old maps confirm, because they make a distinction between brick structures (shown in red) and stone or concrete (shown in grey). Perhaps the fact that the first row went over budget discouraged O’Neill; perhaps he had a falling-out with de Bobula. He would not be the last.

Houses on Frank Street, Greenfield

Nevertheless, de Bobula got quite a bit of publicity mileage out of this little project. He regarded himself as an apostle of concrete, pushing back the conservative forces of the lumber and steel industries, and he continued to quote the figure of $1500 for a six-room concrete rowhouse. You will pardon a lengthy quotation from The Cement Era, October, 1907:

By all odds the leading architect in the matter of concrete construction is Titus de Bobula, who has made for himself a conspicuous place in the ranks of American designers by the excellence and variety of concrete buildings he has planned lately for Greater Pittsburgh. Mr. De Bobula comes from Buda Pest, Hungary, where concrete construction has been well known for many years. Starting some four or five years ago in this city with concrete building he fought down the prejudice against them and today his structures are recognized throughout Pennsylvania as architectural models as well as striking examples of durability and cheapness.

Architect De Bobula’s work has not been confined to flats and dwellings, although he has built a large number of them. He built the Greek Catholic church at Duquesne,12 a suburb of Pittsburgh, which cost $35,000, and is among the most artistic edifices in Allegheny county. This was the first reinforced concrete building in the county built for public uses. It has a concrete roof and trimmings and has stood since 1904, as a fine example of the new style of construction.

Other public buildings which were erected by Architect De Bobula are the Greek Catholic church in Carnegie, Pa., costing $30,000, the Roman Catholic church in Glassport, Pa., costing $25,000, and a large parish house in Glassport. The roof of the Glassport church is supported by arched ribs and the structure is noted over the county for its fine architectural appearance.

Mr. De Bobula has also built 17 flats and more than score of dwellings in the Twenty-third ward of Pittsburgh. These buildings have cost him at least 10 per cent less than frame structures would have cost. Where a row of dwellings is to be built so that cast iron forms can be used Mr. De Bobula claims that the cost is 40 per cent less than the average brick veneer house, as much of the carpenter and plaster work can thus be eliminated.

Speaking of concrete and its uses in architectural construction, Mr. De Bobula said recently:

“There is a notable defect in the building laws of Pennsylvania, which do not provide for the use of concrete. They specify that foundation walls must be at least 18 inches thick, although an eight inch concrete wall is amply heavy enough for the ordinary house. A few building inspectors are reasonable enough to allow for this discrepancy in the statutes, but most of them hold to the rigid letter of the law, to the utter disregard of common sense. It is perfectly safe to erect concrete buildings more than ten stories high, if self-supporting steel frames are used to guard against the great wind pressure. You will see more high concrete buildings in Pittsburgh every year, for in spite of the strenuous efforts of steel and lumber men to thwart the concrete idea it is growing at an amazing pace and has taken fast hold upon the conservative investor. Modern six-room houses can be built of concrete, in a row for $1,500 each, and if they are detached they will cost only $2,000.”

Architect De Bobula has patented a reinforced concrete door and window frame which is soon destined to take an important place in the new style of buildings. This is composed of a thin wire mesh covered with concrete, and makes a door no heavier than the ordinary wooden door, and very much more durable. They can be tinted and finished to accord with the colors in any room. The new invention will be manufactured in the Pittsburgh district next year.

Architecturally, de Bobula seems to have been proudest of his churches, to judge by the fact that he signed their date stones prominently in his own florid Art Nouveau lettering.

The date stone on St. John the Baptist, Munhall

He had reason to be proud. He brought Pittsburgh a whiff of Budapest Art Nouveau, and there was nothing else like it in our landscape at the time. Our other modernists—Frederick Scheibler and Kiehnel & Elliott are the only really important names from the same period—were heavily influenced by German styles. De Bobula’s sweeping curves and imaginative forms were unique in Pittsburgh.

First Hungarian Reformed Church, Hazelwood

St. John the Baptist Greek Catholic Church, Munhall

We should point out that St. John the Baptist, above, was done in 1903, the year de Bobula arrived in Pittsburgh. The confidence of it is breathtaking. Not only did our 25-year-old architect produce a design that has held up for 120 years and still causes architectural historians to gush today (see the Society of Architectural Historians article on St. John the Baptist), but he made one that was like nothing anyone had ever seen before, mixing up textures and elements from wildly different historical styles with a jazzy disregard for dissonance.

In addition to churches and economical small houses, de Bobula claims to have produced apartment buildings and commercial buildings, and here much research remains to be done. According to a city architectural survey, the Everett Apartments in Shadyside are by de Bobula, and they certainly would look at home in Budapest:

Everett Apartments, Shadyside

However, there is conflicting evidence about this building, because it seems that S. A. Hall, or A. S. Hall (depending on the sloppy Linotyping of the trade journals), drew plans for an apartment building at this site.

The city also identifies the remarkable six-floor building at 418 First Avenue downtown as de Bobula’s work, though the identification is tentative. It is dated by the city as before 1910, but a 1910 plat map seems to show a much smaller building there.

418 First Avenue

We have therefore not identified anything in or near Pittsburgh by de Bobula from after 1907. In 1912, though, we find Titus de Bobula still listed as an architect, now at the Oliver Building, with cable address Debobula.13

Much of what de Bobula designed was never actually built. For example, he was among the top Pittsburgh architects invited to submit a design in the competition for the new $100,000 Tree of Life Synagogue on Craft Avenue, but the winner was D. A. Crone.14 (That synagogue later became the Pittsburgh Playhouse, and was only recently demolished.) That de Bobula was drawing plans for synagogues will take on a keen irony when we read the rest of his story.

Some of de Bobula’s proposed designs were exhibited at the Pittsburgh Architectural Club’s 1905 exhibition, including this design for Montefiore Hall, reproduced in the exhibition catalogue:

With an unlimited budget, Titus de Bobula would have changed and weirdened Pittsburgh’s architectural landscape, and it would have been for the better. We must give him that credit before we move on to the personal side of his story.

Now, why do we not find much architecture by de Bobula after 1907? It may be because he was too busy with other things. Up through 1907 or so, de Bobula seems to have been busy and successful as an architect. But there is some evidence that he imagined himself becoming more than that.

First, we can see that he had a taste for expensive living almost from the beginning of his career.

In 1904, de Bobula was tried for voluntary manslaughter, accused of running down a woman in his automobile in Duquesne, where the Greek Catholic church he designed was going up. That he had an automobile in 1904 shows he was living on a pretty high budget: it was four years before the Model T was introduced and cars became affordable for the masses, and even then “affordable” was a generous term and “masses” meant upper middle class. In 1904, a car was definitely a rich man’s indulgence.

This case appears to have set precedents in automotive law, and it was carefully watched by car owners everywhere. After some legal back-and-forth, de Bobula was acquitted. Here is a short report from The Rural New Yorker, December 31, 1904:

Titus De Bobula, a well-known architect of Pittsburg, Pa., was placed on trial in the criminal court December 7, charged with voluntary manslaughter. He was accused of running down and killing Mrs. Mary Stauffer with his automobile. The coroner’s jury exonerated him, but a son of the dead woman made information for murder and the grand jury returned a true bill. He was acquitted on trial December 9. The case is an unusual one, and automobilists generally are interested in its outcome.

The Pittsburg Post reported that Mrs. Mary Stauffer “was knocked down in Duquesne by an automobile, which DeBobula was driving, and received injuries which caused her death the same evening. The case attracted no little public attention, as the speed at which the machine was going at the time of the accident was an important point at issue.”15 “No little attention” is right: the case was front-page national news. It pops up in papers from Topeka to Allentown.

After 1907, de Bobula seems to have diversified his interests. By 1910 Titus de Bobula was identified in the newspapers, not as “the well-known Pittsburgh architect,” but as “general manager of a large coal concern.”16

This was the year he married Eurana Dinkey Mock, which is the sort of name one wishes one had made up. Her aunt was married to Charles M. Schwab, the steel baron. The marriage was quite sudden, and it put de Bobula in the national news again, as we see from the front page of a San Francisco paper:

Miss Genevieve [?] Mock, not yet out of her teens and the favorite niece of Charles M. Schwab, and Titus de Bobula, a well known Pittsburgher, eloped one month ago and are now in Europe on their honeymoon. The story has just leaked out through their friends.

Schwab is said to have been greatly vexed over his niece’s marriage, as he had planned a brilliant career for her.17

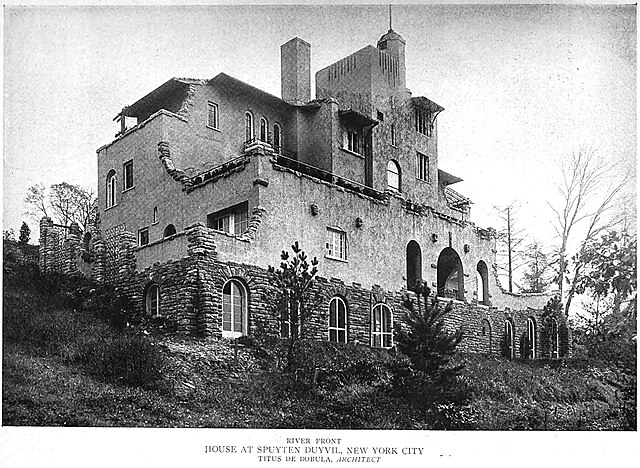

The couple were married at two minutes past midnight on June 1 in New York, making Mrs. de Bobula the city’s first June bride.18 The young couple moved to New York. There we know (so far) of one extravagantly eccentric mansion Titus designed on the palisades overlooking the Harlem and Hudson Rivers in the Spuyten Duyvil section of the Bronx. It was the top feature in the June 2, 1920, issue of The American Architect, where we can see multiple photos and floor plans.

Here at last we see Titus de Bobula free to let his imagination run wild. Unfortunately, we do not believe the house still stands: it has probably been replaced by an apartment building.

In spite of the high-budget project at Spuyten Duyvil, it seems as though de Bobula was not making enough to keep up with expenses. He apparently tried to make up his income by frequently putting the screws on his wife’s uncle. In 1919, de Bobula sued Schwab for slander, and Schwab admitted in court that he had called de Bobula “dishonest, incompetent and a blackmailer.”19 “I’d give Bob a million dollars right now if he’d jump out of a window.”20

“But Mr. Schwab added there was nothing malicious in the utterance or that he intended thereby to injure de Bobula.”21

The suit was dismissed after Schwab asserted, among other things, that he had advanced $208,831 to de Bobula, which had never been returned.

Shortly afterward, the de Bobulas moved to Hungary, where de Bobula “gambled successfully in foreign exchange,” said the Boston Globe in 1923.

He and his wife live in luxury, their principal care being a wolf hound, which is housed in a special suite and waited on like a spoiled child.22

The story of Titus de Bobula has been growing odder as he grows older, but most readers probably did not expect us to introduce Adolf Hitler into De Bobula’s biography. That, however, is just what we are about to do.

In Hungary de Bobula turned Fascist and spent his time plotting against the Hungarian government. “At one time,” the Boston Globe tells us, “Bobula edited the ‘American,’ an anti-Semitic paper here of little circulation, but vicious in its attacks.”23

In 1923, he was arrested for a bungled attempt to overthrow the government in synchronization with Hitler’s bungled attempt in Bavaria.

On November 7, one day before the outbreak of the “beer-hall revolution” in Munich, a detachment of Hungarian soldiers surrounded the Vienna express train coming from Budapest and arrested one of the passengers, Dr. Francis Ulain, a member of the Hungarian Parliament. They found in his possession a passport to Munich and an “international agreement” signed, as between the Bavarian and Hungarian states, by Dr. Adalbert Szemere and Titus von Bobula on behalf of Hungary, and visaed by Herr Doehmel, “diplomatic delegate,” on behalf of Bavaria. Ulain’s errand was to have the agreement signed by Adolf Hitler as the supposed representative of the sovereign Bavarian state.24

The Boston Globe article is a little hysterical, so we may not be able to rely on it when it tells us this:

Bobula expected to become ruler of Hungary and invested $15,000 to back the putsch plans. He has earned the ridicule of all Budapest, for his operations were ludicrously infantile.25

It is quite certain, however, that de Bobula was smack in the middle of a plot to turn Hungary into a Fascist dictatorship. He was thrown in jail and bailed himself out with $15,000 worth of his wife’s jewelry—jewels her uncle had given her. It did not bring the two men any closer.26

It also appears, by the way, that the first reports in Europe had De Bobula as Henry Ford’s brother-in-law. (One American millionaire is pretty much interchangeable with another.) These reports reached Jewish publications in America. Ford, whose anti-Semitic rantings were well known to Jews in Europe, sent a message to the Jewish Telegraph Agency in New York saying, “I don’t even know Titus de Bobula.”27

Here we may pause for a moment and ask ourselves how our architect got into this position. We have seen abundant evidence that, brilliant architect though he was, he was even more a flimflam artist. Did Titus de Bobula flimflam Hitler? Was Hitler convinced that he had the distinguished Hungarian-American coal baron, financier, architect, and newspaper publisher Titus de Bobula on his side, and therefore success was assured?

By the 1930s de Bobula was back in the United States, dealing in German-made sub-machine guns.28 He was affiliated with a Captain Tauscher in the B & T Munitions Company, and their activities came up in senate committee hearings in 1935 on the munitions industry. “There have been a hundred of those guns brought from abroad so far this year, and there is apparently no control of it,” said one witness.

Senator Bone. How are they shipped in?

Mr. Young. They are shipped in as small firearms.

Senator Bone. To whom?

Mr. Young. To the B. & T. Munitions Co.

Senator Bone. What are they, what sort of an outfit are they?

Mr. Young. It is an outfit who is endeavoring to market them throughout the country.

Senator Clark. What does B. & T. stand for?

Mr. Young. It is a partnership arrangement owned by Captain Tauscher and Colonel De Bobula.…

Senator Clark. What kind of a gun is it?

Mr. Young. It is a German gun, I think, known as “Schmeisser gun.”

Senator Clark. That is a competitor of the Thompson submachine gun?

Mr. Young. Yes, sir.29

From here it is a little hard to trace the spiraling weirdness of de Bobula’s career. It pops out at us in little items like this:

Big Crime ‘Arsenal’ Proves False Alarm

NEW YORK, Aug. 2 [1939] (AP).—Police thought they had stumbled on a crime arsenal or the cache of a band of terrorists when they found a quantity of tear gas and shrapnel “bombs” and “dynamite” sticks in the basement of a Bronx home.

The mystery blew up, however, when the tenant, Titus de Bobula, returned home last night. He explained the explosives were “dummies” used in his munitions business and had been put in the cellar three years ago by his wife.

If you are thinking to yourself that this “dummies” explanation could be true, but could also be the work of a practiced con man oiling his way out of a scrape with a slick tongue, you are thinking some of the same thoughts Father Pitt is thinking.

In that same year, his wife’s aunt died, leaving most of her estate to her husband. Mrs. de Bobula filed objections to the will, alleging “fraud and undue influence” on her aunt.30 From this item we can probably draw some conclusions about the de Bobulas’ relations with the Schwabs.

We also read that he drew sketches for the structural parts of Nikola Tesla’s fantasy death rays. A book published in 2002 says that the sketches are in the Tesla Museum, which is in Serbia.31

And that is the last we hear of him as an architect. He lived the last couple of decades of his life in Washington, and he seems to have fallen into relative poverty. His wife stuck with him, and we may gauge her relations with the rest of her family by noting that she sued to have her aunt’s body thrown out of the family mausoleum nine years after her aunt had died.

PITTSBURGH, Feb. 21.—A $510,000 damage suit filed here yesterday demanded that the body of Steel Magnate Charles M. Schwab’s widow be disinterred.

Filed against a suburban cemetery company and two relatives of Mrs. Schwab, the action was brought in Common Pleas Court by Mrs. Eurana Mock de Bobula, wife of a Washington architect.

Besides the casket of Mrs. Schwab. the suit also asks removal of five others from the $50,000 mausoleum in nearby Monongahela Cemetery.

Named as defendants are Mrs. de Bobula’s sister, Mrs. Mary Mock Walter of Bethlehem, Pa.; Mrs. Marshal Reid Ward of Wayne, Pa., and the Monongahela Cemetery Co.

Mrs. Ward was Mrs. Schwab’s sister and is the aunt of both the plaintiff and the other defendant, according to Mrs. de Bobula’s attorney, Dale T. Lias.

Mrs. de Bobula claims she and Mrs. Walter both own the mauoleum but that she was not consulted in the burial of six bodies there.

The cemetery property was inherited jointly from their mother, Mrs. Jeanette Elizabeth Mock, Mrs. de Bobula claims. Mrs. Mock, who was Mrs. Schwab’s sister, in turn inherited it from her mother. Mrs. M. E. Kinsey. who bought in in 1895.

Mrs. Schwab died in 1939.32

De Bobula suffered a stroke that left him half paralyzed, but he still had a con man’s instincts, as we find in the early 1950s, when he tried to shake down the CIA. An internal CIA memo explains that he had been involved in a West Virginia real-estate transaction with a woman who happened to work for the CIA, had a disagreement with her, and tried to hold the CIA responsible for his perceived loss. (The names were redacted by the CIA when the memo was released to the public.)

On 11 October 1952 there was referred to this office a registered letter addressed to the Director from one Titus de Bobula requesting the intercession of this Agency in a private matter between Mr. de Bobula and an employee of CIA, Miss ———, arising from a transaction with respect to a tract of West Virginia land. We undertook to investigate the matter and to date have discovered nothing reflecting discredit upon our employee. As far as we are able to tell, Miss ———, through her gratuitous actions, is involved with a litigious crank. We replied to Mr. de Bobula’s first letter stating that our investigation showed a certain basic misunderstanding of a purely private nature in which CIA could not concern itself. Since that time we have received several further letters from Mr. de Bobula, in vein similar to the first, becoming progressively more insulting to CIA. We have firmly informed him that we wish to have nothing further to do with the matter. The latest development is that Mr. de Bobula has sued out a criminal complaint against Miss ——— and a Mr. ——— not an employee, who is also involved. We understand that his complaint relates to the manner in which title to the West Virginia land was acquired by Miss ———. We have put Miss ——— in touch with counsel, and have indicated our interest to help where we reasonably can.

De Bobula was not one to give up easily. One of the letters in the correspondence (this one dated January 30, 1953) was addressed to Allen W. Dulles, the CIA director, at his own home. Mr. Dulles duly filed it. It paints a very sad picture—partly intentionally sad to provoke sympathy, but also sad because here we see the aged and nearly invalid Titus de Bobula looking back over his life and citing his greatest accomplishment: “Planned and built a cathedral 50 years ago.” (By this time, the church of St. John the Baptist in Munhall was the cathedral of the Ruthenian Archeparchy of Pittsburgh, so the statement was technically correct.)

Dear Mr. Dulles,

Please, overlook this letter being addressed to your home. There is a reason for it.

Attached, you will find copies of a few letters. They will partly show the strain and enmity under which my wife suffered for many years. The man, Seeblienko, mentioned in them, is a continual irritant. I do hope that Mr. Houston is not going to be misled by his machinations.

You are entitled to a short resumé of our life before you could judge impartially. I am in my 75-th year, my wife 10 years younger. I was a wealthy man to find myself, together with my wife, in a firnished room, without ready funds. AND not through our fault. If you will requisition the file, from Mr. Houston, it might shed some light on the subject. I mention it only shortly, that it deals with a CIA employee, or employees, who engineered a landgrab of 10,000 Acres, who owe us now hundreds of dollars, which we miss.

Over a year ago, I suffered a stroke of my entire right side. Since then my wife was my nurse but she is breaking under the strain, especially now, when both of us suffer from influenza. It is a reprehensible and unamerican situation against two sick people.

A few days ago, Mr. Houston wrote, in which he disclaimed any responsibility but sympathized with our plight. It seems to me, that the CIA should not be carrying an added burden through the inhuman land grab of an employee or employees.

My wife joins me in the hope of an impartial and human and just review of the entire case. I did not have the honor of a personal hearing by Mr. Houston. I do ask you for same.

Mrs. de Bobula just mentions to me that she was in the 1911 class of Bryn Mawr together with Margaret Dulles. She does not know her present address.

I am, sincerely,

de Bobula

These are the last words we have so far from Titus de Bobula, though he lived nine more years. They paint a sad picture—all the sadder because they humanize him, and they humanize Mrs. de Bobula as well. From the outside they look like monsters. But we know one relevant fact. She loved him. She could have had everything by giving up the crazy Hungarian con man. Instead, she stuck with him, and she took care of him when he was incapable of taking care of himself. As awful a man as he was, he was worthy of love; and as awful a woman as she was, she gave it to him.

So there you have him: Titus de Bobula, oily adventurer, coal baron, bad driver, Nazi plotter, would-be dictator, arms dealer, litigious crank, and architectural genius. What you make of him is up to you. But it is certain that his buildings are works of art, and old Pa Pitt will stand in front of any bulldozer that threatens them. It is also certain that the forward-thinking architects of Pittsburgh and the nation looked to him as the leader in reinforced-concrete construction, so his effect on our landscape would be hard to overestimate. We must take the good with the bad and the sane with the nuts.

Here is a list of buildings by Titus de Bobula still standing in our area. The list is probably incomplete, and Father Pitt hopes to add to it with more research.

418 First Avenue, before 1906 (attribution uncertain)

St. John the Baptist Greek Catholic Church and Rectory, 10th Avenue and Dickson Street, Munhall, 1903

Apartment building (“Glen Tenement House”), Elizabeth Street and Gertrude Street, Hazelwood, 1903

First Hungarian Reformed Church, Johnston Avenue, Hazelwood, 1903–1904

St. Emory’s Church, 425 South Arch Street, Connellsville (now Faith Bible Church)33

Rowhouses on Frank Street, Greenfield, 1905

St. Michael’s School and parish house, 1135 Braddock Avenue, Braddock, 1904

St. Peter and St. Paul Greek Catholic (now Ukrainian Orthodox) Church, 220 Mansfield Boulevard, Carnegie, 1906

Everett Apartments, 5420 Ellsworth Avenue, Shadyside, 1907. There is conflicting information about this building: S. A. Hall, or A. S. Hall, appears to have drawn plans for a building at this site.

If the Everett is by De Bobula, then Father Pitt has a suspicion that the apartment building at 404 Walter Street in the Allentown neighborhood may also be by de Bobula, based on its notable similarities to the Everett.

A 1981 “Guide to Historic Hungarian Places in Pittsburgh” (PDF) says that the First Hungarian Reformed Church in Hazelwood was “designed and constructed by the firm of Titusz Bobula.” If this came from the church records, it suggests that De Bobula did not use the “de” among his fellow Hungarians. The same source also says that De Bobula donated the original bell for the church. ↩︎

“Services of a Hungarian Architect have Been Secured by W. B. O’Neill & Co.,” Marietta Daily Leader, June 20, 1901, p. 1 ↩︎

“Convent Will Occupy Putnam Hall After it is Moved,” Marietta Daily Leader, August 20, 1901, p. 5. ↩︎

“Another House Raiser,” Marietta Daily Leader, September 26, 1901. ↩︎

Cambridge Jeffersonian, November 28, 1901, p. 3. ↩︎

Zanesville Times Recorder, August 20, 1902, p. 7. ↩︎

“People’s Wants,” Zanesville Times Recorder, August 22, 1902 ↩︎

Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, February 24, 1904, p. 119. ↩︎

“Able Architects the Authors of City’s Architectural Beauty,” Pittsburg Press, Saturday, April 29, 1905. Other articles in the same issue confirm that the Press headline writer had discovered alliteration and gone mad with power. ↩︎

A row of six of these can be seen on Frank Street at Lilac Street in Greenfield; as you will see below, Father Pitt believes no more than nine were built. ↩︎

O’Neill (misspelled in the article) was owner of the Dispatch. ↩︎

Now gone, replaced by a larger church in the 1950s. ↩︎

International Cable Directory of the World, 1912, p. 425. ↩︎

Pittsburg Press, January 29, 1906: Architects O. M. Topp, Titus de Bobula, D. A. Crone, Charles Bickel and S. B. Eisendrath have been selected to prepare competitive plans of the $100,000 synagogue, to be erected on Craft avenue, near Fifth avenue, Fourteenth ward, for the Tree of Life Congregation. Henry Jackson is chairman of the building committee. ↩︎

Pittsburg Post, Saturday, December 10, 1904. ↩︎

“First June Bride Weds at 12:02 A. M.,” New York Times, Thursday, June 2, 1910 ↩︎

San Francisco Call, Friday, July 15, 1910. ↩︎

“First June Bride Weds at 12:02 A. M.,” New York Times, Thursday, June 2, 1910 ↩︎

“Schwab Disclaims Malice in Reply to Slander Suit,” New York Tribune, Thursday, August 7, 1919. ↩︎

“Bobula Married Niece of Schwab,” Boston Globe, Sunday, November 18, 1923. ↩︎

“Schwab Disclaims Malice in Reply to Slander Suit,” New York Tribune, Thursday, August 7, 1919. ↩︎

“Bobula Married Niece of Schwab,” Boston Globe, Sunday, November 18, 1923. ↩︎

“Bobula Married Niece of Schwab,” Boston Globe, Sunday, November 18, 1923. ↩︎

The Nation, December 19, 1923, p. 721. ↩︎

“Bobula Married Niece of Schwab,” Boston Globe, Sunday, November 18, 1923. ↩︎

“Schwab Asks Niece to Bring Dogs Home,” The (Baltimore) Sun, Monday, April 14, 1924. ↩︎

Das Jüdische Echo in Munich, December 21, 1923: “Henry Ford bestreitet die Unterstützung des europäischen Antisemitismus.” ↩︎

“Capt. Tauscher Has Prospered, Servicing Gas and Bomb Stations for Years,” Dayton Daily News, Friday, September 21, 1934. ↩︎

Hearings before the Special Committee Investigating the Munitions Industry, United States Senate, Government Printing Office, 1935 ↩︎

Los Angeles Times, April 7, 1939: “Mrs. Schwab’s Will Attacked,” on the front page. ↩︎

Thomas Valone (editor), Harnessing the Wheelwork of Nature: Tesla’s Science of Energy. Adventures Unlimited Press, 2002. ↩︎

“$510,000 Damage Suit Asks Disinterment of Schwab Widow’s Body,” (Washington) Evening Star, February 21, 1948, p. A-3. ↩︎

This is a new addition to the list. As far as old Pa Pitt knows, recent historians have missed this attribution, but it is quite certain. A glance at the building is convincing enough, but we also have the evidence of the Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, August 31, 1904: “Architect Titus de Bobula, Farmers’ Bank Building, has awarded to the Connellsville Planing Mill Company the contract to erect St. Emory’s Roman Catholic church, at Connellsville, Pa. Estimated cost, $15,000.” We might add that it was a Hungarian congregation. ↩︎